✍️:.Dr.Manzoor Ah Rather

The history of Kashmir is not a story bound within its own valley, it is a narrative woven through centuries of cultural contact, trade, religious exchange, and human migration. From the prehistoric settlements of Burzahom to the grand temples of the early medieval period, the land has witnessed continuous interaction with the outside world. Artefacts, inscriptions, and architectural remains tell us that Kashmir has always been connected to far-off lands, from Mongolia and China to the plains of present-day Pakistan.

The Narvaw Valley, located in the Baramulla district, holds a particularly rich chapter of this story. It is here that Fatehgarh Temple stands, silent yet eloquent testimony to centuries of cultural, religious, and political developments. The site is closely linked to the Buddhist heritage of the valley and, in the oral traditions of the local people, to the great Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang). This Writeup is based on the detailed oral and historical insights shared by Bilal Ahmad Lone, a young historian from Baramulla, in an interview conducted by Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Rather.

Kashmir’s Ancient Cultural Contacts

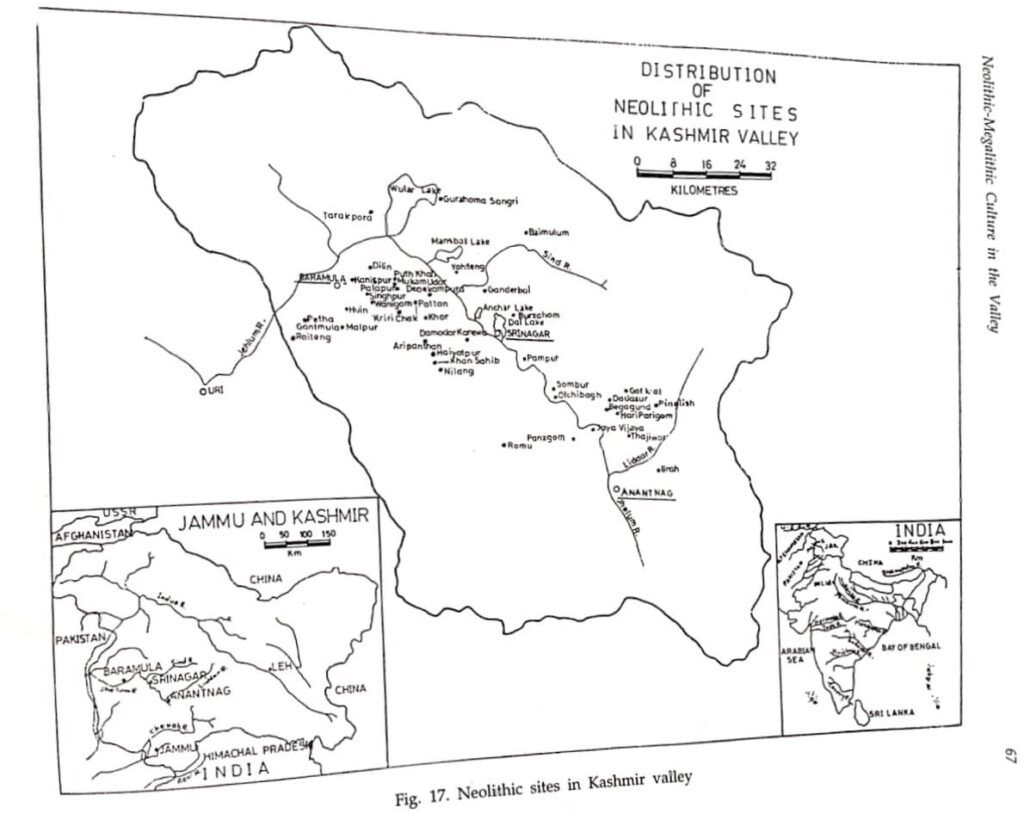

When speaking about the ancient history of Kashmir, Bilal Ahmad Lone begins at the very roots, Burzahom, the prehistoric site near Srinagar. Archaeological excavations there have shown clear evidence that human settlement in Kashmir dates back to the Neolithic period.

One of the most telling facts is that the pottery discovered at Burzahom bears striking similarities to pottery found in far-off regions such as Northern Sindh (Pakistan), Taxila, and other sites in Pakistan, China, and Mongolia. These similarities are not coincidental, they demonstrate that Kashmir maintained cultural links with the outside world even in prehistoric times. Ideas, technologies, and material culture flowed in and out of the valley long before the rise of classical civilizations.

Baramulla: The Western Gateway

Bilal describes the Baramulla district as the “western gateway of Kashmir.” Since ancient times, the routes passing through Baramulla, particularly through Narvaw, served as major channels for travellers, traders, and even invaders entering the valley. This route functioned as an ancient cart road, linking Kashmir with Central Asia and the Indian plains. Along this strategic route arose temples, stupas, and settlements that served not only as religious centers but also as resting places for merchants and pilgrims.

The Fatehgarh Temple: Historical and Archaeological Significance

At the heart of this history stands the Fatehgarh Temple, located in the Narvaw Valley. Bilal emphasizes its importance both historically and archaeologically. The surrounding landscape, particularly the village now called Buddhamulla, was once fertile land supporting a thriving settlement. The archaeological evidence strongly suggests that this was a major Buddhist center from as early as the 3rd century BCE.

Nearby, at Zehanpura, stand stupas that share design similarities with the famous Sanchi Stupa in central India. This connection further underscores the Narvaw Valley’s role as a vibrant Buddhist cultural zone.

Early European Observations

The Fatehgarh Temple first entered the record of European explorers in 1823, when William Moorcroft and George Trebeck visited and noted the site. Moorcroft later described it briefly in his influential travel work Travels in the Provinces of Hindustan and Punjab.

In 1848, Alexander Cunningham, later celebrated as the “Father of Indian Archaeology,” visited the temple. He cited Trebeck and Baron Hugel, noting that the local Muslim population referred to it as “Batt Dal”, meaning “the idol house.” Cunningham, while sometimes critical of what he called the “ignorance” of locals, nonetheless relied heavily on the oral traditions preserved by Kashmiri Muslims for much of his knowledge about the site.

Other scholars, such as Vigne, Hugel, and Cowie (the latter authoring Notes on the Temples of Kashmir), compared the Fatehgarh Temple with other notable Kashmiri shrines. Cowie linked it architecturally to the Buniyar Temple, while Cunningham saw resemblances to Pandrethan Temple in Srinagar. These scholarly debates suggest that Kashmiri temples, though unique, shared structural, material, and stylistic affinities.

Architectural Features and Materials

Bilal explains that four different types of stone and building materials were used in the temple’s construction, all sourced locally. The craftsmanship reveals a blend of indigenous skill and Central Asian influence, pointing to Kashmir’s position as a crossroads of cultures. The diversity in architectural features across Kashmiri temples suggests a shared artistic vocabulary, adapted to local conditions.

Hiuen Tsang and the Village of Hieun

The Narvaw Valley is deeply tied, in local memory, to the visit of the great Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) in the 7th century CE. It is believed he entered Kashmir through this Drangbal gateway and spent nights at Ushkura, not far from Fatehgarh.

Historians such as S. L. Shali (Kashmir and Archaeology Through the Ages) and R. C. Agrawal (Kashmir and Its Monumental Glory) identify a village in this area called Hieun in ancient times, likely linked to the pilgrim’s name. Oral accounts say that in those days, Hieun was the only major settlement in the Narvaw Valley.

Conclusion

Hiuen Tsang himself, a devout Buddhist scholar, came to Kashmir in search of sacred Buddhist scriptures. His work Si-yu-ki: Records of the Western Regions gives a detailed account of his two-year stay in the valley and its religious sites.

Historical Layers: From Buddhism to Lalitaditya

The Fatehgarh Temple likely originated as a Buddhist learning center during the early centuries BCE and CE. It may have continued in use for centuries, eventually being associated with King Lalitaditya Muktapida of the Karkota dynasty (8th century CE), a great builder who commissioned major temples like Buniyar and Parihaspora. Some scholars credit him with reconstructing or enhancing the Fatehgarh site.

Archaeological Survey of India Excavations

In 1978, the Archaeological Survey of India conducted excavations at Fatehgarh, uncovering significant finds, including a Maheshwari image and a remarkable Trimurti sculpture, unique among Kashmiri temple art. These finds indicate the site’s continued religious significance long after the Buddhist period, reflecting a layered history of worship and adaptation.

The Renaming of Hieun to Heewan

The final thread in this story comes from the mid-20th century. During the tenure of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad (Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, 1953–1964), the leader visited Hieun Village to address a large public gathering. The people of Narvaw, largely unaware of the village’s historical association with Hiuen Tsang, understood “Hieun” in Kashmiri to mean “dog.”

Seeing the awkwardness and sensing the need for a more dignified name, Bakshi declared publicly that from that day forward, the village would be called Heewan, meaning “Jasmine garden.” The new name quickly replaced the old in everyday use, and the connection to Hiuen Tsang faded into memory, except among historians and archaeologists.

From prehistoric pottery to Buddhist stupas, from medieval kings to modern political leaders, the story of Fatehgarh Temple and Heewan village encapsulates the many layers of Kashmir’s history. The temple is not merely a relic, it is a witness to the valley’s role as a cultural bridge between India, Central Asia, and beyond.

The Narvaw Valley’s archaeological and oral heritage remind us that history lives not just in written chronicles, but in the stones, names, and memories passed down through generations.

Bilal Ahmad Lone, a young historian from Baramulla with a postgraduate degree in History from the University of Kashmir, has devoted much of his scholarly energy to uncovering the layered history of the Kashmir Valley. His expertise extends from Kashmir’s prehistoric roots to its early historic Buddhist heritage, and his knowledge blends both archaeological findings and oral traditions.

In this conversation, recorded in June 2021 on Narvaw Literary Society for the present writeup, Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Rather speaks with Bilal Ahmad Lone about the prehistoric and early historic significance of Narvaw, with a particular focus on the Fatehgarh Temple, the Buddhist settlements of the region, and the curious historical episode of how the village once known as Hieun came to be called Heewan.

About the Columnist

Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Rather popularly known as Narvaw Walla, is a Kashmiri academic, researcher, and cultural activist from Baramulla. He founded the Narvaw Literary Society in 2020 and actively works to preserve Kashmiri literature, oral histories, and cultural heritage. His research focuses on Kashmir, oral narratives. He Was associated With The Partition Museum Amritsar, India.