The Jhelum Valley, winding its way through the historic district of Baramulla, cradles within its curves remnants of an ancient and spiritually rich civilization. Among these relics lies the Zehanpura Buddhist site, also referred to in older sources as Jaimpur, a name derived from Jamadagnipura, indicating Vedic roots. Located 10 kilometers below Baramulla, opposite Ghantamulla, the site lies forgotten amidst grassy mounds and rice fields, bordered by a gently flowing Jhelum River and disrupted only by a narrow canal that bisects it.

Modern archaeological eyes recognize the importance of these mounds, long perceived as innocuous humps by locals but now widely identified as ancient stupas, potentially among the oldest Buddhist structures in the Kashmir Valley.

Historical Identity and Mythical Associations

The site of Zehanpura, located on the right bank of the Jhelum River approximately 10 kilometers downstream from Baramulla, is steeped in layers of history, myth, and cultural memory. Its identity has evolved over centuries, from a possible Vedic settlement to a Buddhist center, and finally, to a site of mythic intrigue among the local population. To understand Zehanpura’s true significance, one must trace both its historical etymology and the mythical narratives that have surrounded and shaped it. The importance of Zehanpura is also geographical, it lies on the ancient trade and pilgrimage route from the North-West Frontier Province (Gandhara) into the heart of Kashmir. This location undoubtedly contributed to its prominence as a cultural and religious node in antiquity.

The Name ‘Jaimpur’ and Vedic Connections

In the writings of S. L. Shali, the place known today as Zehanpura is believed to be the apabhramsha (a linguistic distortion or degeneration) of Jamadagnipura, which later came to be referred to as Jaimpur. The name Jamadagnipura is directly connected to the Vedic sage Jamadagni, one of the revered rishis of the Rigvedic tradition and the father of Parashurama, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Jamadagni is often associated with penance, asceticism, and wisdom, and places bearing his name are typically marked as ancient centers of learning or meditation.

Jamadagni is one of the revered sages (rishis) in Hindu mythology and Vedic literature, especially known as one of the Saptarishis (Seven Great Sages) in some traditions. He is closely associated with the Bhṛigu lineage and is famously known as the father of Parashurama, the sixth avatar of Vishnu. Jamadagni belonged to the Bhargava lineage (descendants of Bhṛigu), a prominent family of Vedic sages. His lineage is deeply connected with asceticism, divine wisdom, and fierce commitment to dharma.

Jamadagni was a powerful sage who attained immense spiritual knowledge and yogic powers through tapasya (penance). He is credited with possessing the divine cow Kamadhenu, which could fulfill any wish and provide endless supplies of food and wealth.

The transformation of Jamadagnipura → Jaimpur → Zehanpura is emblematic of how ancient names are localized over time, often blending with the dialects, oral languages, and cultural transitions of the communities inhabiting the region. This suggests that the area may have been settled or sanctified long before the emergence of Buddhism, possibly as a hermitage or a spiritual site during the Vedic period.

The Myth of Kamadhenu: The Divine Cow of Abundance

Local tradition and classical references further enrich the site’s spiritual aura. According to oral lore and regional belief, Kamadhenu, the celestial cow in Hindu mythology who is said to fulfill all desires, once descended upon Zehanpura. It is believed that her footprint is preserved on a rock near the site, a divine imprint that sanctifies the land and confirms its association with sacred fertility, divine generosity, and abundance.

Kamadhenu’s symbolic presence at Zehanpura offers several interpretive possibilities:

It connects the site to Hindu cosmology, particularly the mythological age of the rishis and divine beings.

It reinforces the belief that the land was once fertile, sacred, and blessed, making it a suitable location for either ashrams or stupas.

The footprint acts as a physical link to mythology, much like the Buddha’s footprints (Buddhapada) found in other Buddhist sacred sites across Asia.

The intertwining of Brahmanical mythology with the archaeological presence of Buddhist stupas is a recurring theme in Kashmir, reflecting the layered religious history of the region, where Buddhism, Shaivism, and Vaishnavism often coexisted or evolved successively.

Early Archaeological Investigations and Significance

The first formal archaeological interest in Zehanpura was sparked in 1925–26, when a preliminary excavation was undertaken. Despite high expectations, the excavation did not yield substantial findings, and the nature of the mounds remained indeterminate. However, the then Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) expressed great enthusiasm for the site, hopeful that deeper exploration would lead to important discoveries.While the initial effort did not produce significant structural revelations, numerous copper coins were unearthed from the nearby site of Ghantamulla, bearing imprints of rulers such as the Huna chiefs, Queen Didda (958–980 CE), and King Harsha (1089–1101 CE). This coinage evidences continued settlement and activity at or near Zehanpura from early medieval Kashmir to the Rajatarangini period, thus confirming the site’s long-term relevance.

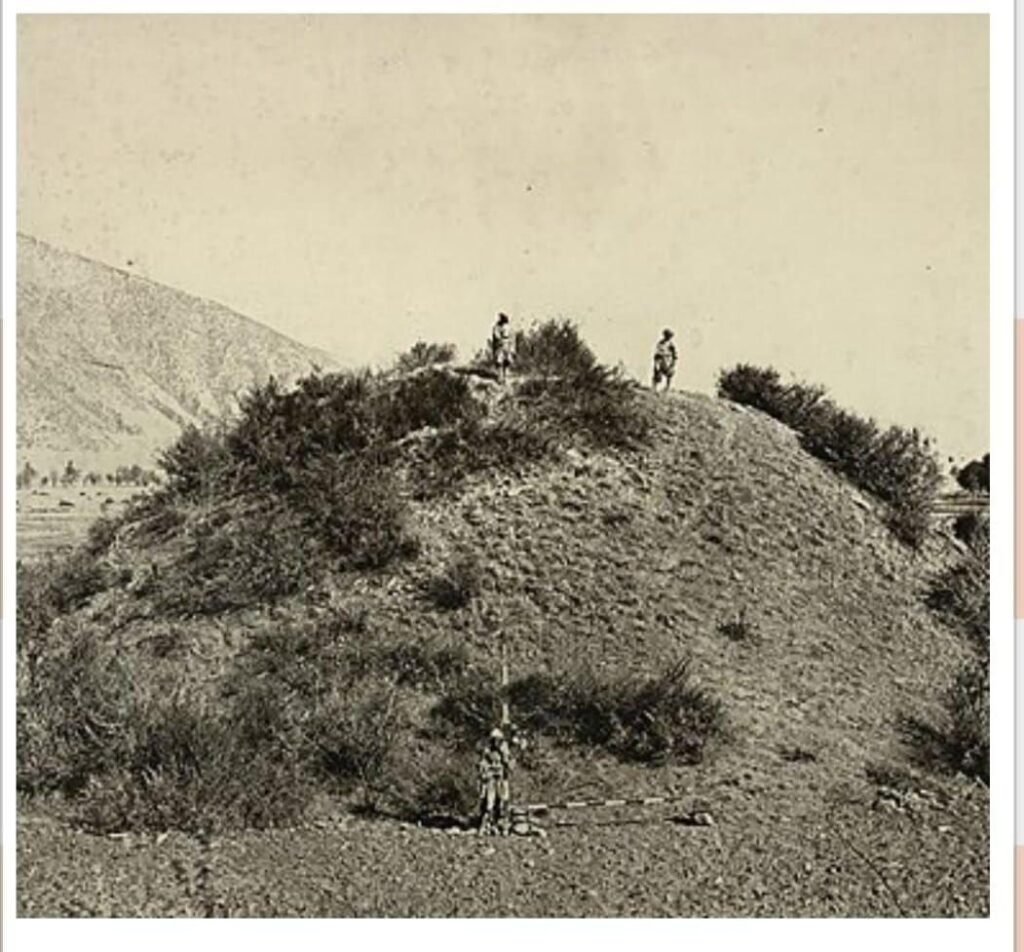

The Three Mounds: Remnants of Buddhist Stupas

a. Layout and Physical Description

As documented by R. C. Agrawal in Kashmir and Its Monumental Glory, the three stupas at Zehanpura are structurally significant:

Stupa No. 1

Located 1 km southwest of Zehanpura village.

Square in plan, constructed in three terraces using konjoor stone.

The top terrace is approximately 8 meters square, and the total height from the current ground level is about 8 meters.

The base is 3 m wide and grounded, suggesting a formal ritual foundation.

Stupa No. 2

Found 200 meters west of the first stupa.

Heavily damaged, likely due to treasure-seeking activities.

Present height is between 4 to 5 meters, with a partially collapsed drum.

Stupa No. 3

Lies 200 meters south of Stupa No. 1, on the left side of a canal and on the right of the river Jhelum.

The largest of the three, rectangular in plan, and features western offsets, seen on the western side.

Constructed from konjoor stones with lime mortar. It is the biggest of all the three stupas and has the remains of three terraces. The top terrace measures 8 m square and 10 m high from the present ground level. it rises 10 meters high with three terraces.

A damaged section on the southern side indicates the original entrance.

b. Architectural Style and Comparisons

The hemispherical style of the stupas and their terraced design resemble Stupa No. 3 at Sanchi, indicating Pan-Indian Buddhist architectural influences.

Built upon flat terraces, they predate the Karkota Dynasty (8th century CE) and are possibly attributed to the later Gonandiya dynasty.

c. Patronage and Dating

The Rajatarangini by Kalhana mentions Amritaprabha, queen of Ranaditya, a 6th-century ruler. She is said to have patronized Buddhism, and it is plausible that the stupas were built during her reign (third quarter of the 6th century CE).

Oral Traditions and Local Beliefs

Interestingly, the archaeological silence of Zehanpura is contrasted with vivid oral traditions. Local elders believe the site is inhabited by spirits or curses and is best avoided, especially after dusk. These cautionary tales, passed down for generations, have limited access and exploration, unintentionally preserving the structures from mass disruption.

Children from surrounding villages are often seen playing on the mounds, unaware of their heritage, while the adults keep their distance out of respect or fear.

While archaeology may rely on stratigraphy and stone, the soul of Zehanpura lives in the whispers of its people. Among the villagers of Zehanpura, Ghantamulla, and the nearby hamlets nestled along the Jhelum, there exists a deeply entrenched oral tradition, a narrative of wonder, warning, and mythical allure.

It is widely believed and orally passed down through generations that beneath the ancient mounds of Zehanpura lies a hidden treasury, a plough made of pure gold and untold riches buried deep within the earth. This golden plough is said to be a sacred artifact, tied to an era when the land was blessed with divine fertility and abundance. In some variations of the tale, it is believed to have been used by celestial beings or ancient kings who tilled the sacred soil of Zehanpura in reverence to Kamadhenu, the wish-fulfilling cow whose footprint is said to mark the area.

However, the myth is not one of easy reward. Alongside the legend of immense wealth comes a dark and forbidding condition, to access the golden plough and its accompanying treasures, a seeker must be willing to sacrifice his most beloved offspring.

This tale of extreme devotion and tragedy has created a psychological veil over the site. Locals refer to it as a haunted or forbidden place, not because of apparitions, but because of the spiritual weight of the sacrifice demanded. Over time, the story has become a moral allegory, a caution against greed, a reflection on love and loss, and perhaps, a subconscious mechanism to protect the site from desecration.

The myth further reinforces why, even today, elders discourage children from playing too long on the mounds, and religious men avoid performing rituals near the site. A few anecdotal stories even speak of men who dreamt of digging the site, only to wake up in fear or fall mysteriously ill, a folk motif of divine retribution common in cultures that guard ancient sacred grounds.

This oral tradition of treasure guarded by moral consequence is not unique to Zehanpura; similar legends appear across South Asia. Yet what makes this one particularly poignant is that it overlays a Buddhist archaeological site, traditionally associated with peace, renunciation, and non-attachment, with a tale of ultimate sacrifice for material gain. This paradox itself is a cultural commentary, possibly reflecting a clash between fading Buddhist memories and resurgent local mythologies shaped by centuries of socio-religious transition in Kashmir.

In this light, the legend of the golden plough may be read not just as fantasy, but as a living archive of memory, morality, and myth, encapsulating the local population’s awe, fear, and reverence toward their forgotten heritage.

Disruption and Lost Monasteries

Accounts from locals mention the destruction of konjoor stone buildings during canal construction, hinting at the loss of monastic complexes that once accompanied the stupas. Such damage, mostly undocumented, adds to the tragic fate of many early Buddhist monuments in the region that have vanished due to development or neglect.

Archaeological Context of Baramulla District

Zehanpura is not an isolated relic. It forms part of a broader network of archaeological sites in Baramulla district, many of which reflect Buddhist and early Shaivite-Hindu influence:

Parihaspora: Capital of Lalitaditya Muktapida; hosts monumental ruins of stupas and temples.

Tapar Pattan: Rich in temple remains.

Kanispura: Here Kanishka built the city, which was named as Kaniskapura, modern Kanispora Baramulla.

Ushkura: An early Buddhist site with relics and votive stupas.

Fatehgarh Narvaw: Site of local archaeological discoveries; its name often linked to fort ruins.

Naranthal: Near Drangbal Baramulla, with potential ancient temple foundations.

Buniyar: Close to Zehanpura, often cited for cultural intersections.

Bandi Dathamandir: Presumed temple site, little explored.

Ferozpur Drang (Tangmarg): Known for megalithic structures and early traces.

Zehanpura stands at the threshold of this sacred geography, perhaps a gateway between Gandhara and Kashmir, offering evidence of the cultural osmosis that shaped the Valley’s religious landscape.

A Landmark Discovery Unfolds: Zehanpora Excavation Begins

Earlier this week, as I casually scrolled through news updates on my mobile, a headline on Kashmir Despatch caught my eye, it announced the long-awaited archaeological excavation at Zehanpora, a site that has intrigued scholars and locals alike for decades. What made this update truly historic was that it marked the first-ever independent excavation project undertaken by the Department of Archives, Archaeology and Museums, Jammu and Kashmir, in collaboration with the Centre of Central Asian Studies (University of Kashmir). The moment felt like witnessing history being reclaimed.

Approved by the Archaeological Survey of India under Rule 25 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Rules (1959), the project is being carried out with the support of the Capex Budget of the J&K Government. According to the flash, the excavation is under the direct supervision of Mr. Kuldeep Krishan Sidha (JKAS), Director of DAAM, while the technical lead is Dr. Mohammad Ajmal Shah, Assistant Professor at the University of Kashmir. Their combined leadership ensures that both administrative experience and academic expertise guide this sensitive cultural undertaking.

The site, Zehanpora, located on the banks of the Jhelum River, holds immense historical promise. It lies not far from Kanispura and Ushkura, ancient towns associated with the Kushan kings Kanishka and Huvishka, and features prominently in Kalhana’s Rajatarangini. Scholars believe this area was once part of a thriving Buddhist corridor connecting Kashmir to Central Asia, with monastic sites, stupas, and trade links enriching the region’s cultural life.

The mobile update hinted that the Zehanpora site may offer archaeological evidence spanning the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, possibly including terracotta remains, stone structures, or even inscriptions shedding light on the religious and artistic life of ancient Kashmir. Some believe it might even help trace the footsteps of Xuanzang, the famous 7th-century Chinese pilgrim who documented Buddhist Kashmir in rich detail.

What struck me most was how the excavation is not just a dig, it’s a declaration of cultural revival, a reminder that Kashmir’s past is not buried, but waiting to be told anew. This three-phase project, slated to run from 2025 to 2028, could redefine our understanding of Kashmiri Buddhism, trade routes, and regional identities. For now, that single news flash on my phone screen feels like the start of something profound: a journey into our layered past, one discovery at a time.

Conclusion

Zehanpura represents a hidden chapter in the Buddhist history of Kashmir, a site where myth and history converge, and where archaeological silence masks a rich cultural narrative. Its rediscovery and protection are not merely academic concerns but an essential step toward reclaiming Kashmir’s pluralistic past. Its positioning on a historical Gandharan trade route underscores its potential role as a transit hub for pilgrims, monks, and traders moving into the Kashmir valley. Moreover, Zehanpur’s mounds might help trace the continuity and transformation of Buddhist practice in the region—particularly from Gandharan Mahayana influences to Kashmiri Vajrayana developments in later centuries.

To the historian, it is a relic of the classical age.

To the archaeologist, it is a site of promise.

To the local, it is a mystic mound shrouded in lore.

To us, it must be a national heritage—valued, studied, and preserved.

References

- Shali, S. L. Kashmir: History and Archaeology Through the Ages.

- Agrawal, R. C. Kashmir and Its Monumental Glory.

- Kalhana. Rajatarangini (translated by M. A. Stein).

- Kak, R. C. Ancient Monuments of Kashmir.

- ASI Reports, 1925–26 (Preliminary Excavations).

- Oral Testimonies from Zehanpura and Ghantamulla Villagers in Baramulla J&K

About the Author

Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Rather popularly known as Narvaw Walla, is a Kashmiri academic, researcher, and cultural activist from Baramulla. He founded the Narvaw Literary Society in 2020 and actively works to preserve Kashmiri literature, oral histories, and cultural heritage. His research focuses on Kashmir, oral narratives. He Was associated With The Partition Museum Amritsar, India.